Grupo CoSensores: Accessible Monitoring Tools for Communities

- Ashley Eugley

- Mar 23, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 24, 2023

"We do this project for real transformation in the lives of the people"

Kevin Poveda Ducón

Monitoring tools are a central component of any community science project. They may be as simple as human senses (e.g., what people see, smell, hear, and feel), or more technologically complex (e.g., computer-based sensing devices, pH test strips). Monitoring tools provide valuable information about the environments that surround us, and the extent of our understanding is often predicated upon the type of tools we have access to. Imagine trying to discern the severity and composition of air pollution based on human senses alone. You may know that there is something unusual going on—you can see and smell smoke and your eyes burn—but you do not know much more. The same story holds true for water pollution; your tap water may taste funny and have a strange color, but these cursory observations do not tell you what is really going on. You may not know if the air is safe to breathe or if the water is safe to drink. And what about the forms of pollution that you cannot see, smell, taste, or sense?

Humans are affected by the health of their environments, but we are not the most fine-tuned instruments when it comes to detecting and understanding pollution: our experiences tend to be more symptomatic than conclusionary. As subjective evidence (i.e. sensory data) does not always hold up when matters of policy-making, litigation, and action are concerned, it is important to involve tools that can provide more precise estimates about the composition of our surroundings. With some limitations, these tools help support and verify subjective human experiences in a capacity that may be more easily translated into action.

Examples of monitoring tools — Photos: Ashley Eugley

From left to right: TemTop Air Quality Monitor (Estimates the concentration of particulate matter (PM) in the air); Phosphate Test Kit (Detects the approximate concentration of phosphate in a water sample); Air Quality Bucket (Takes grab samples of air for lab-based testing. Notably, this device was modeled after the Louisiana Bucket Brigade's EPA-Approved "Buckets" and was designed and deployed by Bard College students (including me) in a 2019 Air Quality Research course.)

Technological monitoring tools enhance our understanding of the bigger picture, but they are not without their faults. Foremost of these is that they are inaccessible and expensive, require frequent maintenance and calibration, tend to involve complex procedures, and may produce results that are difficult for non-scientists to interpret. Such factors may inhibit community science projects from employing technological monitoring tools, especially if the projects have low budgets.

These are the problems that Grupo CoSensores wants to alleviate for community monitoring projects in Argentina. Founded in 2013, CoSensores aims to “develop technologies that allow organized community groups to perform social and environmental assessments in a simple and affordable way, and therefore contribute to the implementation of restoration procedures or actions leading to material improvements in their quality of life” ("Grupo" 2022). CoSensores involves citizens in the entire process of developing monitoring strategies—from problem identification to data collection, data analysis, and solution implementation. This focus ensures that the scientific expertise offered by CoSensores prioritizes and serves the expressed needs of the citizens, and that the tools they design are accessible. Admirably, CoSensores is motivated by the potential for their research to encourage political action and lead to “concrete improvements in the quality of life of the community” (CoSensores 2016). Increasing access to scientific tools for monitoring is one step on the long path towards a more environmentally just, healthy, and equitable future.

"Los miembros fundadores de CoSensores estaban unidos al “anhelo de realizar tareas de investigación que pudiesen servir a las necesidades de comunidades fuera de la Universidad. Esto tal vez haya surgido un poco desde cierta conciencia social y otro tanto como un intento de acortar la gran distancia que habitualmente separa a las tareas científicas que se realizan en la academia, de ese afuera muchas veces ausente en la agenda de quienes trabajan dentro ella” (CoSensores 2016).

The founding members of CoSensores were united by the “desire to carry out research tasks that could serve the needs of communities outside of the University… [they wanted] to shorten the great distance that habitually separates scientific tasks that are carried out within the academy from the outside which is often absent from the agenda of those who work within it.”

Citizen Science & Pollution in the Matanza-Riachuelo Basin

Grupo CoSensores partners with communities, organizations, activists, and citizen science projects to develop scientific monitoring tools that are accessible and relevant to social and environmental realities. For example, in 2013, CoSensores began collaborating with Movimiento Campesino de Santiago del Estero-Vía Campesina (MoCaSE-VC). MoCaSE-VC was founded in 1990 by a group of various regional peasant associations that wanted to defend their land, ensure food sovereignty, and advocate for comprehensive agrarian reform in the areas surrounding the Matanza-Riachuelo River Basin (MRRB) (Ashpa Sumaj 2012 as cited in Grupo CoSensores 2016). This area has a long history of pollution from industrial activity and farming practices, resulting in high levels of contaminants like arsenic, pesticides (e.g. glyphosate), and lead in the air, soil, and drinking water (Grupo CoSensores 2016). According to an article from 2020, it is estimated that 25% of children living near the MRRB have lead in their blood (Gomiz 2020). Clearly, these contaminants threaten the well-being of communities in the region and have concerning health implications.

Through concerted and ongoing collaboration, CoSensores and MoCaSE-VC developed a portable biosensor (see note below) that uses micro-algae to detect glyphosate concentrations in water samples. This device helps the community to understand the threat posed by their water and to keep track of glyphosate pollution over time. CoSesores prioritized making a “cheap, relatively fast and easy-to-handle tool that would allow a comprehensive survey, both temporally and spatially” that could also be used, maintained, and replicated by the community autonomously (CoSensores 2016). This ensured that the technology could serve the needs of the community over a long span of time without demanding the support of scientific professionals. While more information does not automatically lead to material improvements in quality of life, health, and well-being, collecting evidence and monitoring our surroundings helps inform our behaviors. Furthermore, leveraging this information can put pressure on decision-makers to take action.

Note: A biosensor is a device that uses components like bacteria, algae, or plants to detect a certain environmental variable. Notably, conventional lab-based techniques often rely on highly sensitive, technical machinery and procedures in addition to large, immobile equipment (Whitacre 2012 as cited in CoSensores 2016). Such devices are very difficult for non-scientists to use (or even gain access to) and most often cannot be brought into the field.

Incidentally, CoSensores is not the only citizen science project that is working closely with communities in this highly polluted area of Northern Argentina. Prior to meeting with CoSensores, I spoke with Guillermina Actis and Leticia Castro Martinez of another citizen science project, CoAct: Ciencia Ciudadana para la Justicia Ambiental en la Cuenca Matanza Riachuelo. According to their website, in the MRRB "there are stories of collective struggles to recover the enjoyment of the river, promote better living conditions and repair environmental damage that unequally affects the people of the basin. CoAct Justicia Ambiental is a social citizen science action that seeks to put these concerns and transformation actions at the center of research activities." Actis and Martinez recommended the book Flammable: Environmental Suffering in an Argentine Shantytown by Javier Auyero and Débora Alejandra Swistun—an ethnography that documents the impacts of extreme pollution on the Flammable neighborhood (Villa Inflamable)—to learn more about "life amidst hazard, garbage, and poison" in this area (Auyero and Swistun 2009).

This video compiles perspectives from participants of CoAct's "Que Pasa Riachuelo?" (QPR) workshop. It asks and answers the question: what is the Matanza-Riachuelo River Basin for you? Responses focus on the high level of pollution and the way that pollution influences the community's ability to enjoy the river. To learn more about QPR, check out their website.

*For English Subtitles: Settings > Subtitles > English (auto-generated)*

A Closer Look at the Tools & Approach of CoSensores

CoSensores works with community groups to develop monitoring tools. Their methodology involves two workshops with community members. First, they collectively identify the problem and conduct preliminary tests. Second, they share and discuss results, the advantages and limitations of the methods, and potential strategies to manage the issues they detected in their research ("Grupo" 2016).

*For English Subtitles: Settings > Subtitles > English (auto-generated)*

CoSensores makes scientific monitoring tools available for community needs. These devices can be constructed and deployed without professional scientific knowledge, enhancing the capacity for local investigation, supporting activism, and informing decision-making.

Photos: CoSensores via Lombardi 2019

“Hemos aprendido que la labor científica comprometida con la sociedad adquiere sentido cuando los saberes académicos y los no académicos se colocan en pie de igualdad, donde científicas y campesinas trabajamos codo a codo” (CoSensores 2016).

We have learned that scientific work committed to society makes sense when academic and non-academic knowledge is placed on an equal footing, where scientists and peasants work side-by-side.

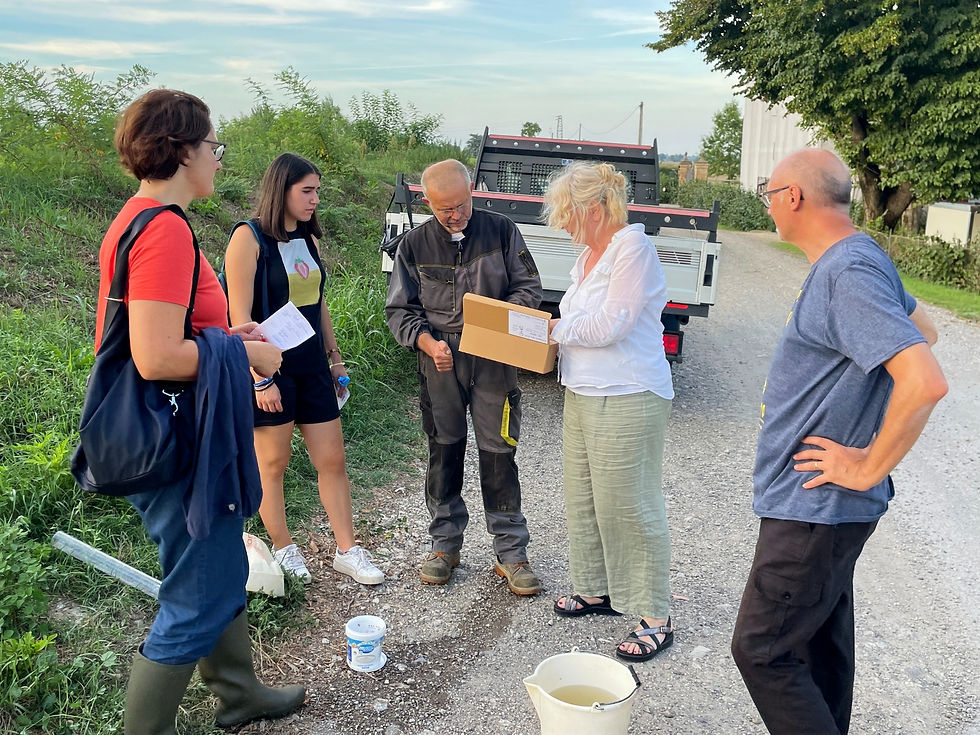

I met with Kevin Poveda Ducón at the Universidad Nacional de San Martín on the outskirts of Buenos Aires to discuss Grupo CoSensores. He demonstrated how some of their monitoring devices work and shared about CoSensores' approach, philosophy, hurdles, successes, and goals.

This device is called a colorimeter. It precisely detects the color of a water sample using a flash of light and a sensor and sends the results to a mobile app. It can be used to identify the concentration of phosphate, nitrate, and other compounds in a water sample.

Monitoring tools provide valuable insight on the environments that surround us. With them, we can discern the severity and composition of pollutants, plan for averse weather, and make informed decisions that allow us to optimize our health. By collaborating with communities to make these devices more accessible and relevant to local needs, CoSensores is helping to make science a tool for the people.

“CoSensores es, a la fecha, un grupo consolidado, efectivo y funcional con objetivos, enfoques, formas, estructura y organización que se diferencian de la práctica científica institucionalizada; una experiencia que pensamos y sentimos, que abre una ventana para pensar el camino a una ciencia comunitaria, de y para la sociedad” (CoSensores 2016).

To date, CoSensores is a consolidated, effective and functional group with objectives, approaches, forms, structure, and organization that differ from institutionalized scientific practice; it is an experience that opens a window to think about a path for community science that is of and for society.

Thank you to Kevin Poveda Ducón, Guillermina Actis, and Leticia Castro Martinez for meeting with me and sharing about these incredible community science projects.

————————

Bibliography

Auyero, Javier and Debora Alejandra Swistun. Flammable: Environmental Suffering in an Argentine Shantytown. Oxford University Press, 2009.

CoSensores. 2016. "Tierra Y agrotóxicos: Un Enfoque Coproductivo En problemáticas Socioambientales." Cambios Y Permanencias, 7:181-219. https://revistas.uis.edu.co/index.php/revistacyp/article/view/7052.

Gomiz, Natalia. "LAS AGUAS BAJAN TURBIAS. Herramientas desde abajo: organizaciones sociales impulsan un relevamiento ambiental comunitario."La Izquierda Diario, 3 July 2020. https://www.laizquierdadiario.com/Herramientas-desde-abajo-organizaciones-sociales-impulsan-un-relevamiento-ambiental-comunitario

"Grupo CoSensores – Sensores Comunitarios." In Citizen Science Solutions Mapping, 2nd Edition. Argentina Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, 2022. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/fichascienciaciudadana_en_2ed.pdf.

Lombardi, Vanina. "Unidos para evaluar el agua." TSS — Universidad Nacional de San Martín, 12 September 2019. https://www.unsam.edu.ar/tss/unidos-para-analizar-el-agua/.

Comments